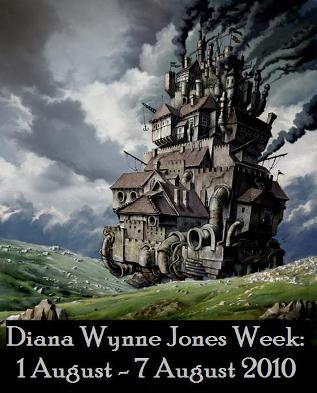

Before I could write up my impressions of Diana Wynne Jones' novel Fire and Hemlock, based on the Tam Lin and Thomas the Rhymer stories, I learned that Jenny believes it's even better on rereading, and since this was my first time through it, all I can give you is first impressions.

Like most readers, I was appalled with the characterization of the main character's (Polly's) parents, who neglect her to an extent almost unbelievable even in fiction--at one point, leaving her stranded in a strange city with no food, money, or shelter. And like any reader, I was enchanted with the magic that allows Polly and her friend Tom Lynn to imagine things and then see them come true. Another pleasure for readers is seeing Tom sending books to Polly, and hearing about what she learns from reading them, along with her occasional ignorant mistake before she has read something, like the time she asks if she can call him "Uncle Tom."

As in any novel by Diana Wynne Jones, one of the incidental pleasures is in the little slices of psychological verity, like this one:

"Polly came away from the Headmistress to find that the rest of the school regarded her as a heroine. This is nothing like being a hero, which is inside you. This was public. People asked for her autograph and wanted to be her friend. She came out of school at the end of the afternoon surrounded by a mob of people all trying to talk to her at once. It made Polly's head ache."

The title image, of a painting in which the young Polly could see images that the older Polly does not (at least for a while, until she gets her memories of Tom Lynn back) also seems to me to have some psychological reality. How many times as a child did you look at a crack in the ceiling or the uneven pattern of tiles on a floor and see a face or figure? Do you still see them? I sometimes do, especially when I'm tired or running a fever, but I think when I'm feeling well I'm like most other adults and don't have the same kind of attention or time to notice.

I enjoyed the first part of the ending, in which Polly reconciles her two sets of memories--one with Tom Lynn included, and one without, which she traces back to a promise she made to forget him--and has an adult discussion with him, for the first time, about the risks of loving him and involving herself in his world.

The second part of the ending, though, with a test involving a pool, was confusing. While still thinking about it, I was confronted with the reactions of other celebrators of Diana Wynne Jones week (Eva, for one) who also didn't understand the ending after their first reading. I found the ending of Fire and Hemlock slightly disappointing, but after consideration decided that perhaps such disappointment is an appropriate response to the ending of a story about the tricky ways of the Queen of the Fairies. Who ever comes away from such an experience feeling satisfied? You're lucky to come away at all, as the story of Tam Lin amply testifies.

The other result of this first reading is that my memory was tickling me with the central image of the empty autumn pool, and I found out why when I read that DWJ based the image on one from T.S. Eliot's Four Quartets (see Two Sides to Nowhere and her links to DWJ's essay "The Heroic Ideal").